Disability Pride Month

July is Disability Pride Month!

Officially recognized in 2004, Disability Pride Month started with a parade in Boston, MA, in 1990 to celebrate the passing of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). The law prohibits discrimination against people with disabilities, including employment, transportation, accommodation, and access to government services. Disability Pride Month is an opportunity to celebrate the intrinsic worth and meaningful contributions of people with disabilities, honor their inherent dignity and inalienable rights, elevate their visibility, and celebrate their achievements.

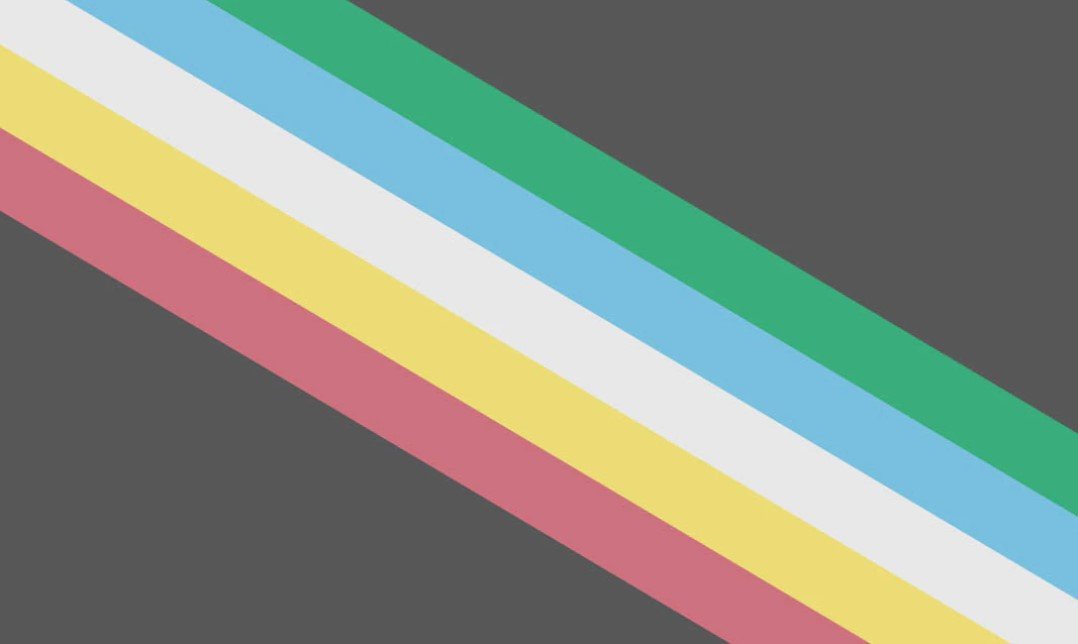

The Disability Pride Flag was designed by Ann Magill and updated in 2021 to ensure accessibility. Each color of the Disability Pride Flag represents a different type of disability: physical (red), cognitive and intellectual (yellow), invisible and undiagnosed (white), psychosocial (blue), and sensory (green). The charcoal background symbolizes mourning and rage for the victims of ableist violence and abuse, and the colored bands are placed diagonally to convey persons with disabilities “cutting across” societal barriers.

Here are some ways you can support the disability community (from QI Creative):

Ableism is discrimination against disability.

At its core, Ableism is the assumption that typical abilities are superior to disabilities, and the harmful stereotypes, misconceptions, and generalizations that follow (Access Living, n.d.). It can emerge in different conscious and unconscious forms including (but not limited to):

Environment

Public transportation without adaptations or seating for disabled passengers, or able-bodied passengers seated in disabled spaces

Lack of signage and navigational aids for various physical, cognitive, and sensory disabilities

Websites without easy-to-read fonts and color schemes, described audio, closed captions, or described images, relying only on auto-generated captions versus hiring transcription

Storefronts and curbs without accessible entryways, poorly designed or constructed adaptations

“Ramps” with harsh slants and inclines beyond the accessible usage of wheelchair users

Adaptive public transit services that require significant time in advance to reserve and wait for, or assistance from someone else to reserve

Event venues without quiet rooms/sensory rooms for staff and attendees

Language

Identity-first vs. Person-first usage*

Infantilization; calling a disabled person brave, heroic, or inspiring for their everyday experiences, or conversely, saying you could not live their lifestyle

Correcting a disabled person for their own identity terms and labels

Using language such as “turn a blind eye/tone deaf/that’s lame/crippling/crazy”

Telling someone “but you don’t look disabled” ; relatedly, compliments that frame positivity in spite of disability (eg. “You’re so _____ for a disabled person”)

Use a disabled dependent, relative, or friend’s experience to position yourself in disability discourse (eg. “As a parent, I…”)

Asking invasive questions about medical history (related, using medical education as clinician to position yourself in disability discourse outside of your professional working relationships and boundaries)

Obfuscating disabled identification (eg. “Handicapable”, “Differently Abled”, “DisAbility”; “People of Determination”)

Societal Attitudes and Behavior

Skepticism that listening to an audiobook is not reading compared to a physical book

When disability accommodations are considered ‘extra’ or ‘burdensome’ when such accommodations should be the bare minimum for equitable access

Stigmatizing movie tropes about disability (eg. When disabled characters are written off for various reasons related to rejecting disability; when disabled characters undergo a change or process to become able-bodied—all generally within the ableist lens that the grief, loss, sacrifice, or change was positive)

Movies portraying disabled characters with non-disabled actors; lack sensitivity to readers

Pushing a stranger’s wheelchair as if to support them without asking first; reaching to engage or pet a service dog that is not yours and is trying to support their owner

Perceiving a lack of eye contact as not listening or disrespectful

Perceiving verbal communication as the only form of communication

Pushing to only achieve verbal communication rather than invest in communication that works for the individual (see AAC Devices and Apps for examples)

Treating deadlines and schedules as sacrosanct, and penalizing those who cannot satisfy artificial time constraints

The rapid adoption of online work and schooling during the COVID-19 pandemic, something many disabled people have advocated for (and subsequently, the reduction or cancellation of virtual options when administrations push for in-person or back-to-office settings)

Lack of workplace compliance with disability rights laws

Not believing in a disability or downplaying the negative outcomes of mishandling one’s health and body, from brain injuries to food allergies

Pushing a disabled person to complete a task or function even as they may openly say they are in pain or distress

* Person-first (“person with autism”) and Identity-first (“autistic person”) are two linguistic descriptions of how we identify people around us. Identity-first is often preferred, in the understanding that using Person-first language continues the history of erasure and stigma around disabilities. Ultimately, it is best to follow how disabled people would like to address themselves.

[Ableism is] a system that places value on people’s bodies and minds based on societally constructed ideas of normalcy, intelligence, and excellence.

Talila A. Lewis, Disability Advocate

Support Disabled Creators

If you consider yourself somewhat of a newbie learning about disability and inclusion, one of the easiest ways to add disabled voices to your spaces is by opening yourself to their channels of communication. Listen, learn, and go from there.

Follow disabled creators on social media. Subscribe to their newsletters and channels. Buy products and books from their stores. Donate to their causes. Give disabled voices platforms and pay for their expertise.

There are many disabled leaders, creators, influencers, collectives, charities, support groups, communities, and more that are doing work year-round. Rather than trying to strike some new approach or fundraiser just for Disability Pride Month, look to where disabled people have already been doing the work—and support them.

Here is a short, non-exhaustive list to get started:

Dr. Jaipreet Virdi – Disability historian

Alice Wong – Creator and amplifier of disability media & culture; the Disability Visibility Project

Liam O’Dell – Journalist, theatre critic, and campaigner (#CCMeIn raising awareness of deaf & hard of hearing people)

The Disabled List – Disability-led, self-advocacy organization curating disabled creators and partnerships

Melissa Blake – Blogger, selfie taker, empowering others with #DisabledJoy

Haben Girma – Deafblind advocate, lawyer, writer, speaker & accessible technology expert

Carly Findlay – Disability rights campaigner and author of Say Hello – Things they don’t tell you about being a Disability Activist

Amit Patel – Author of Kika and Me

Disability History In Canada: Present Work In The Field And Future Prospects by Geoffrey Reaume, PhD

Hannah Barnham-Brown – Doctor, politician, speaker, #RollModel, and disability advocate

And see our previous Black Lives Matter post for a non-exhaustive list of Black and Disabled influencers.

10 Canadian Influencers and Professionals with Down syndrome

Disability Pride Reading Lists

Inclusivity, accuracy, and disabled authorship in books and media depictions are rising. Looking to fill your days under the sun with a book? Check out these book lists, blogs, and articles:

If your disability inclusion doesn’t include intersectionality, it isn’t inclusion.

We mentioned earlier that disability pride does not exist to take or appropriate from other important movements; however, it’s important to include diverse backgrounds and lived experiences in your advocacy.

Some hashtags to explore on your social media may include:

Hashtags are more than just trending words—they have legitimate utility as organization tools among disabled communities.

Related Links:

What we can learn from the Disabled community during COVID-19

Crip Camp – A Netflix original documentary film

IN A BEAT – Original short film by 37 LAINES

Can I Play That – Game writing publication by disabled gamers, exploring accessibility in games for the deaf and hard of hearing; motor/physical accessibility; cognitive accessibility; blind and low-vision; and colorblindness.

Believe, Listen, and Learn

While we’ve mentioned current and historical elements shaping Disability Pride movements, it is important to continue to educate yourself and continue to listen and learn from those around you.

Believe people, unconditionally, when they disclose a disability — don’t accuse people of ‘faking’ their disabilities, their adaptations, their boundaries, and their needs.

Planning an event? Be more conscientious about the venue’s accessibility. A single elevator on the other side of the auditorium is not accessible. Consider lighting and glare, navigation, ambient sound, and access to a multipurpose quiet room. Take accommodation requests seriously.

Talk about disability with your children, and do so with a neutral stance (eg. They are wheelchair users; not, ‘something awful must have happened’). Keep invasive questions about disabilities to yourself, especially if you do not know them well.

Tread lightly and respectfully – Disability Pride Month can be an exhausting period for disabled people, whether or not they speak or advocate publicly.

Explore the policies and practices of your workplaces, the accessibility of your physical location; and with considerations of ableism mentioned earlier in this blog, advocate for change.

Believe, listen, and learn.